Before I stood alone in the “Plywood Palace” reading drunken wall carvings while underwear dangled above my head, I sat at another bar in rural Wisconsin, talking to a welder named Ron.

We sat in the “I Don’t Know"1 Saloon, a well-traveled watering hole near the cabin I stayed for a few weeks of solitude this year. I tell Ron about my plan for the next day— a tour of kitschy dive bars in the Upper Midwest. This is the advice he gives me:

“Don’t get a mixed drink.”

Ron isn’t too impressed with the Plywood Palace.

“It’s a dirty place,” he tells me. Before I can get a word in, he repeats himself. “I mean, it’s really not a nice place.”

I ask for clarity- what makes it so dirty?

“The guy will scoop up the ice with his bare hands. He’ll drop it on the bar floor and put it right back into your drink.” Ron talks with fingers outstretch to illustrate his next point. “The ladies room, no joke, I saw it has a sign above that says, ‘For Emergency Use Only.’”

He laughs, and I join in while we sip our beers in Middle Inlet, an unincorporated community roughly three hours north of Milwaukee. I figure he’s exaggerating for a good Saloon story, and from the comfort of my $12 hamburger, it’s hard to imagine any bar that unsanitary. Ron and I talk into late evening about menthol cigarettes and backpacking Europe, and though I assume his story is fabricated, I’ll remember the warning when I see the Plywood Palace in person.

When I walk in, I’m the only customer. I order a canned Budweiser and try desperately to make conversation with the bartender, who looks roughly three hundred years old. I can’t get more than six words out of him at a time.

“Do you own the place?”

Yep.

“How’d it get like this?”

Burned down.

“Does it get pretty rowdy?”

Oh, no.

“What was it like when it first opened?”

What was it like? he-he-heh… don’t know!

The floor is dirt. The roof has holes. Empty cans pile behind the bar. Dollar bills and underwear hang from the plywood ceiling with thumbtacks. I’m sitting in dreadful silence with Bud when a group of seven people walk through the hingeless back door.

They order Jack and Cokes.

Bud pulls an ice tray from an ordinary home refrigerator. I can’t imagine to what or where it’s plugged in. The door handles are duck tape. I watch in amazement as Bud uses his bare hands to plop three ice cubes into each glass. For the last glass, before my very eyes, he fumbles the ice cube onto the sharpie-ink-covered bar. Back into the glass it goes. Ron, I’m sorry for doubting you.

The group of seven traveled from Minnesota to be here, and they visit once every year as a tradition. We talk for a while about work, travel, and Bud’s distaste for the Minnesota Vikings2, but what I really latch on to is why they come back every year. Russel, a sweet man with paper white hair, says he’d rather be here than some fancy place that makes him feel like he doesn’t belong.

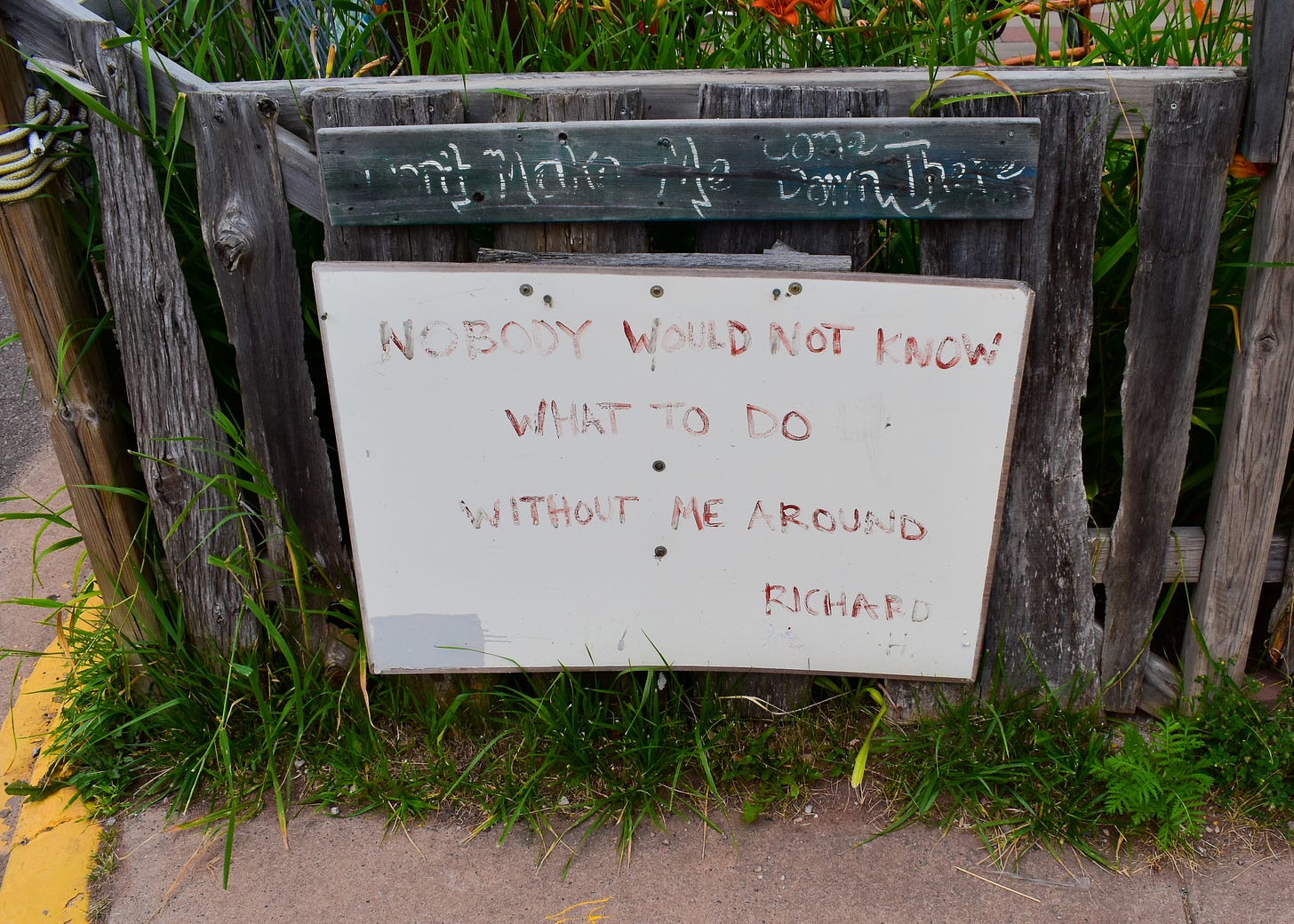

While I can’t in good consciousness say the Plywood Palace is particularly welcoming, especially with a women’s restroom like this:

There’s something to be said about the alienation of a high-end restaurant or cocktail bar. Even ignoring the prohibitive pricing of such places, people choose to spend time in an environment that feels representative of their ideals. If you spend ten hours a day in a concrete factory like Russel, chandeliers and themed dress codes might turn you off.

In the Northwoods, where manufacturing and agriculture’s decline3 left all but the lakeside tourist towns more crater than a community, a dirt-floor bar re- “built” from fire speaks more to your understanding of how the world works. And so Russ feels comfortable. And so Bud’s bar stays open.

Urbanism (which this substack is still about, believe it or not) is about the person-informed transformation of space. Across the continent, across our complicated history, evolving generational power structures determine what shape our communities take. Depending on prevailing economic theory, tastes of the in-group, or solidarity shown by communities who fight for their Right to the City, the places we live can look radically different. Dense rowhomes built in the 1890s, sprawling highway interchanges built in the 1950s, or, I don’t know, crumbl cookies and kung fu tea of the 2010s.

The Plywood Palace is one example of a messy urbanism that refused to let a dive bar die, but it’s not the only one.

This is Tom’s Burned Down Cafe.

Actually, it burned down twice, according to the one of the employees I met, and while you may have to pay a small cover fee to support the live musicians, it’s in an entirely separate league from the Plywood Palace.

Instead of covered in dirt and right-wing political statements, Tom’s is decked in colorful art, inspirational quotes, and signs that welcome people of all backgrounds. And although many of the patrons fit into the yacht-rack-retiree demographic, Tom’s certainly brings a diverse and welcoming crowd. I spent much of my evening in spirited conversation with two women there to support their husbands, each of whom traveled from Minneapolis to perform.

While Tom’s does reap the benefits of a better location within a well-traveled island town, its greater popularity and better all-around experience4 is due to the artistic enthusiasm of the wider Madeline Island community. Not far from Tom’s you’ll find a school of the arts, a museum dedicated to the Islands rich Ojibwe history, and locals who put in the work to make a place like this thrive.

Compared to Tom’s, I can’t help but think the Plywood Palace is as close as you can get to giving up. The best parts of the place, hanging dollar bills and funny inscriptions, are left by its visitors, and the owner simply lets it become a tapestry of debauchery. Tom’s, protected and curated by compassionate locals, becomes another tapestry of creation, but one full of love and excitement for all visitors, including the down-on-his-luck Northwoods Factory worker alongside folks who are queer and indigenous and everything in-between. It’s affectionate, it’s musical, and it’s contagious. One could even call it America as it’s supposed to be.

Towards the end of my night, I stopped to talk with three locals working the door. When I asked what it was like to grow up on an island, one of them explained, “Why would I leave? As far as I can tell this is paradise.”

I’ll leave you with their favorite memories of Tom’s.

Ciara: “As a kid, I’d crawl underneath the bar and find all sorts of loose change and lost jewelry.”

Cora: “Seeing all the local bands play, especially Phantom Tick”

Karen: “Whenever I bring Caps, (Karen’s dog) she runs right up to the people she knows and greets them.”

Happy Monday everyone. Support your local dive bar, and work to make your town a welcoming place.

Meant as the pub-goer’s response when asked, “Where’s you go last night?”

Hanging behind the bar are newspaper clippings not of satisfying wins from the Green Bay Packers, but instead, headlines where the Vikings lost terribly.

Or corporate oligopoly takeover,

That is, if you don’t want someone’s boxers hanging over your head.